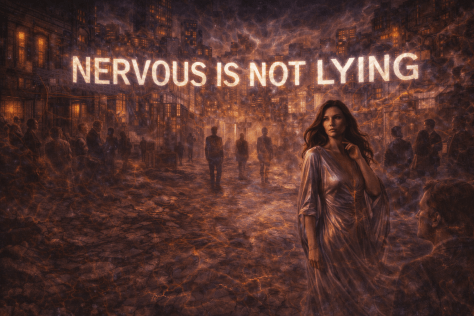

Why modern “lie detection,” interrogation culture, and red-flag hypervigilance are scientifically false, ethically dangerous, and a violation of human rights.

We live in a culture that believes it can see truth on the surface of people. Nervousness is treated as guilt. Inconsistency is treated as deception. Calm is mistaken for honesty. Social consensus is mistaken for evidence. Entire systems—legal, medical, social, and relational—are built on the assumption that stress, behavior, and “credibility” reveal moral truth.

Science says otherwise.

Decades of research show that humans are barely better than chance at detecting lies from behavior. Stress impairs memory retrieval. Interrogation and pressure manufacture false confessions. Polygraphs measure arousal, not honesty. Disability, trauma, and neurodivergence are systematically misread as deception. Groups regularly construct certainty without evidence, producing wrongful judgment, exile, and harm.

In recent years, this same logic has re-emerged in pop psychology and spiritual culture as “red flags”: the belief that hypervigilance and refusal to trust will reveal hidden danger. This article dismantles that superstition and shows how it mirrors interrogation culture—turning fear into authority and intuition into moral weaponry.

At its core, this is not a new truth. It is an old one, now confirmed by science: don’t judge. Not because truth doesn’t matter—but because humans are not built to reliably infer it from behavior, stress, or social reputation. When we forget this, we punish the vulnerable and mistake certainty for wisdom.

This piece is a call to end credibility testing as a cultural norm—and to replace it with epistemic humility, evidence-based inquiry, and basic human respect.

Preface: what this article is—and what it is not

This is an evidence-dense argument against the everyday cultural practice (and many institutional practices) of treating stress physiology, demeanor, and narrative instability under pressure as proxies for deception. It is also an argument that inducing stress states—including sympathetic “fight/flight” overdrive—has been normalized as a tool for extracting “truth,” despite being harmful, coercive, and epistemically unreliable. The harms are not abstract: these practices can ruin reputations, relationships, employment, immigration outcomes, medical care, and legal cases, and they contribute to wrongful convictions, wrongful judgements, discrimination, and wrongful social exile that leaves people isolated and unable to sustain lives.

This article does not claim deception never occurs, or that accountability is impossible. It argues something narrower and more rigorous: human observers and many applied systems are not reliably detecting lying; they are often detecting stress, difference, and vulnerability—and mislabeling it as deceit.

1) The foundational problem: people are barely better than chance at judging lies from behavior

The central myth is simple: “You can tell when someone is lying.” Popular culture teaches this constantly—eye contact, fidgeting, pauses, “inconsistencies,” tone shifts, flat affect, overexplaining, underexplaining, “not acting right.” But the scientific literature is blunt: demeanor-based lie detection performs near chance.

A landmark meta-analysis, “Accuracy of Deception Judgments” (Bond & DePaulo, 2006), synthesized 206 documents and data from 24,483 judges attempting to discriminate lies from truths “in real time” without special aids. The average accuracy was 54%, with people correctly classifying only 47% of lies as deceptive and 61% of truths as truthful (a “truth bias”).

Paper (journal page): https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/2006-Personality-and-Social-Psychology-Review-Accuracy-of-Deception-Judgements.pdf PubMed record: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16859438/

That 54% figure is not a quirky artifact; it has become a reference point because it is repeatedly compatible with later summaries of the deception-detection literature. For example, “Self and other-perceived deception detection abilities…” (Scientific Reports, 2024) describes deception detection accuracy as tending to “hover around 54%,” with truths evaluated more accurately than lies due to truth-bias.

Humility is the first safeguard: obvious lies exist, but ‘I can tell’ is still a dangerous belief.

yes, sometimes deception is blatant—but the cultural habit of trusting intuition, demeanor, and social consensus is still error-prone and ethically hazardous.

Article: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-68435-2

What this means in practice: even before we discuss police interrogation, polygraphs, “microexpressions,” or courtroom dynamics, the everyday act of “reading” someone is already operating at an error rate that is unacceptable for high-stakes decisions. When a culture teaches people to treat “nervous presentation” as evidence, it converts a weak inference into a social weapon.

2) Definitions: the physiology people are misreading as “guilt”

To understand why so many “lie cues” are non-specific, it helps to name the systems being activated.

Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation is part of the autonomic response often described as “fight or flight.” It involves catecholamines (like adrenaline/epinephrine and noradrenaline/norepinephrine), shifts in heart rate, sweating, breathing changes, and altered attention/alertness. It is not a “lying system.” It is a threat response that can be triggered by fear, coercion, sensory overload, pain, trauma memories, authority intimidation, confinement, time pressure, and the sheer terror of not being believed. (Overview: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/fight-or-flight-response)

Stress biology is complex and variable across individuals. Sympathetic patterns differ by stressor type and person. The same outward “tells” can come from many internal states and can be amplified by disability or trauma.

Example review on sympathetic response patterns across stress tasks: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2577930/

The key epistemic point: if a signal is not specific to deception, then treating it as evidence of deception is scientifically unjustified. At best, it is ambiguous data; at worst, it is superstition with institutional authority.

3) Stress as a truth-finding tool is backwards: stress can impair memory retrieval and decision-making

A large body of cognitive and neurobiological research shows that acute stress can alter memory retrieval and decision-making, sometimes in ways that look like “inconsistency,” “evasiveness,” “confusion,” or “non-cooperation.”

A systematic review focused on stress and long-term memory retrieval (“Stress and long-term memory retrieval: a systematic review,” Klier et al., 2020) summarizes the common finding that acute stress shortly before retrieval can impair retrieval, with timing and context mattering (fast responses vs slower cortisol-related effects).

Article (NIH/PMC): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7879075/

A neurobiological review of retrieval under stress (“Acute stress and episodic memory retrieval,” Gagnon & Wagner, 2016) describes how stress hormones and neuromodulators can change hippocampal, amygdala, and prefrontal function in ways that can degrade retrieval performance, especially in free recall conditions.

PDF: https://web.stanford.edu/group/memorylab/papers/Gagnon_YCN16.pdf

Stress can also bias decision-making processes, shifting cognition toward habit-based responding and altering valuation and risk preferences (“Stress and Decision Making: Effects on Valuation, Learning, and Risk-Taking,” Starcke & Brand / later syntheses; one review accessible via NIH/PMC).

Review (NIH/PMC): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5201132/

Why this matters for “lie detection” culture: Many institutions—and many people—treat performance under pressure as a proxy for honesty. But performance under pressure is often a proxy for how someone’s nervous system behaves under threat, how their cognition functions when flooded, and whether the setting provides psychological safety. A stress-heavy interview can easily produce cognitive artifacts that look like deception: partial recall, scrambled chronology, delayed access to details, dissociation, shutdown, contradictory phrasing, or changes as memory reconsolidates.

If you manufacture sympathetic overdrive and then punish people for the cognitive and behavioral consequences of sympathetic overdrive, you are not “detecting lies.” You are creating dysregulation and then moralizing it.

4) Polygraphs: arousal measurement sold as lie detection

A polygraph does not detect lies. It records physiological arousal through channels such as respiration, skin conductance (sweating), and cardiovascular activity. These are not uniquely caused by deception.

The National Research Council (part of the U.S. National Academies) evaluated the evidence in “The Polygraph and Lie Detection” (2003) and emphasized concerns about accuracy—particularly in screening contexts—and the serious problem of false positives (truthful people flagged as deceptive).

National Academies landing page: https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/10420 Example chapter page (false positives discussion): https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/10420/chapter/2 Another chapter discussing specificity and fear of false accusation: https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/10420/chapter/4 Full PDF copy (commonly circulated): https://evawintl.org/wp-content/uploads/10420.pdf

The report explicitly points out that a polygraph outcome can be “positive” because someone is highly anxious—including anxiety driven by fear of being falsely accused—making the signal non-specific to deception (i.e., the test can’t cleanly separate “lying” from “fear”). That is not a technical nitpick; it is the core failure mode.

Disability and trauma implication: If a person’s autonomic system is atypical (e.g., dysautonomia), if they live with chronic hyperarousal, panic, dissociation, medication effects, pain, or trauma triggers, then physiological reactivity is not just “noise.” It is a systematic source of error that can be misread as guilt. In other words, polygraph logic easily becomes ableist by design when used as credibility judgment rather than as a narrow investigative tool with explicit uncertainty bounds.

5) “Microexpressions,” training programs, and the confidence trap

Microexpressions are brief facial movements that can occur during emotional experience. Popular media and some training products market microexpressions as a gateway to detecting deception. The evidence does not support that level of promise—especially not in real-world screening.

A peer-reviewed study evaluating the Micro-Expressions Training Tool (METT), “A test of the micro-expressions training tool: Does it improve lie detection?” (Jordan et al., 2019), reports limited practical value and highlights issues like confidence increases without commensurate accuracy gains.

Public reporting around this research also underscored the concern: training can fail to improve lie detection beyond guesswork while still being used operationally.

Summary: https://www.hud.ac.uk/news/2019/september/mett-lie-detection-tool-flaws-street-huddersfield/ EurekAlert release: https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/888482

This is the worst combination: a tool that increases perceived expertise without reliably improving correctness. The social consequence is predictable: more accusations, more certainty, more institutional reinforcement, and less humility about error.

6) Interrogation is not a neutral interview: it is often designed to produce admissions, not truth

A crucial distinction that everyday culture often collapses is the difference between:

Interrogation: typically accusatory, pressure-based, often designed to obtain an admission/confession. Investigative interviewing: information-gathering, rapport-based, structured to elicit accurate accounts and reduce contamination and false confessions.

Psychological science has documented how interrogation tactics can produce false confessions and how confession evidence powerfully biases downstream decision-makers.

A widely cited “white paper” review, “Police-Induced Confessions: Risk Factors and Recommendations” (Kassin et al., 2010), synthesizes findings about suspect vulnerabilities (e.g., youth, intellectual disability, certain mental health conditions), risky tactics (e.g., long interrogations, false evidence ploys, minimization), and why innocent people can be at distinctive risk.

PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19603261/ PDF: https://web.williams.edu/Psychology/Faculty/Kassin/files/White%20Paper%20online%20%2809%29.pdf

Kassin and colleagues published an updated review, “Police-Induced Confessions, 2.0” (2025), continuing the same central message: false confessions are real, vulnerability is patterned, and reforms are needed.

PDF: https://saulkassin.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/SRP2.0-Confessions-Kassin-et-al-2025.pdf

The American Psychological Association (APA) issued “Resolution on Interrogations of Criminal Suspects” (2014), explicitly addressing false confessions and recommending reforms such as recording and safeguards, with attention to vulnerabilities and the science of interrogation.

What makes this ethically urgent: interrogation tactics often intentionally induce stress, confusion, and helplessness to break resistance. When institutions manufacture sympathetic overdrive, sleep deprivation, cognitive overload, fear, and “learned helplessness” dynamics, they are using the nervous system as a lever. That is coercive. And it is epistemically reckless because it can produce compliant speech rather than truth.

7) Wrongful convictions are not a theoretical risk: false confessions and false accusations are documented at scale

It matters that this is not just “a lab effect.” Real-world data sources tracking exonerations repeatedly identify false confessions and false accusations/perjury as contributing factors.

The National Registry of Exonerations’ 2024 Annual Report (published April 2, 2025) reports, among other factors, that false confessions were involved in a portion of recorded exonerations and that perjury or false accusation was extremely common in those cases.

Report PDF: https://exonerationregistry.org/sites/exonerationregistry.org/files/documents/2024_Annual_Report.pdf

The Innocence Project maintains accessible summaries of contributing factors in its exoneration work, including false confessions.

“Our Impact: By the Numbers”: https://innocenceproject.org/exonerations-data/ DNA exonerations overview with statistics and breakdowns: https://innocenceproject.org/dna-exonerations-in-the-united-states/

These are not merely “mistakes.” When a system treats coerced statements, pressured narratives, or demeanor-based suspicion as truth, it creates a pipeline where error becomes institutional fact.

8) “Credibility” as social consensus is not evidence—and can become coordinated social violence

Many everyday harms do not even require formal legal proceedings. In workplaces, schools, hospitals, activist communities, families, and online spaces, credibility is often treated as a vibe: Who seems coherent? Who seems calm? Who seems likable? Who seems consistent? Who has social allies? Who performs normality?

That is not an epistemology. It is social power wearing the costume of rationality.

Hearsay is not evidence—because reliability collapses when stories propagate socially

In formal law, hearsay generally refers to out-of-court statements offered to prove the truth of what they assert, and it is restricted precisely because it cannot be tested through cross-examination and reliability safeguards. (There are exceptions, but the structure of hearsay doctrine exists because “someone said someone said…” is notoriously fragile.)

In everyday life, people do the opposite: they treat repetition as proof. Group belief becomes “confirmation,” even when the underlying information is unverified, strategically edited, or maliciously coordinated.

Groups can lie

This is the part polite culture avoids saying out loud, but it is true: collectives can falsify witness claims—to punish whistleblowers, to enforce conformity, to discredit marginalized people, to scapegoat a vulnerable person, or to protect a powerful actor. When societies teach that “multiple people saying it” equals truth, they create a weapon: manufactured consensus.

And when credibility is measured by performance under stress, disabled and traumatized people become ideal targets. Their bodies and narratives will “look wrong” to observers trained by myth, not science.

9) Disability, neurodivergence, and trauma: why “appearing deceptive” is often just difference under threat

The discrimination you’re describing is not a side effect; it is structurally baked into how “credibility” is culturally computed.

Research shows that autistic people, for example, can be erroneously perceived as deceptive and lacking credibility due to differences in affect, eye contact, prosody, timing, and social reciprocity—features that many laypeople mistakenly treat as honesty signals.

“Autistic Adults May Be Erroneously Perceived as Deceptive and Lacking Credibility” (Lim, Young, & Brewer; Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders; accessible via NIH/PMC): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8813809/ “Police suspect interviews with autistic adults: The impact of truth telling vs deception on testimony” (Bagnall et al., 2023; NIH/PMC): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10074602/

These findings are not “autism-only.” They generalize to many disability and trauma contexts: people who dissociate, who have autonomic dysregulation, who experience shutdown or freeze, who have alexithymia, who have speech/language differences, who are on medications affecting affect or cognition, who have chronic pain, who are sleep-deprived, who have executive dysfunction, who have Traumatic Brain Injury histories, who have seizure disorders, who have complex PTSD. The core point remains: many so-called deception cues are actually disability cues or stress cues.

10) A section on Zilver’s experiences

I live in a body that does not behave like the credibility fantasies people are trained to worship. I have a severe form of dysautonomia with vagus nerve dysregulation. I’m a human trafficking survivor of ten years. I deal with dorsal vagal and cortical disruption patterns that change what “access to memory” looks like in real time. Under pressure or at times of extreme pain, which is often for me— and especially under accusatory pressure or evaulation—my cognition can fragment. I can lose language. I can shut down. I can get brain fog. I can fail to retrieve linear chronology on demand. That doesn’t mean I’m lying. It means my nervous system is in a threat state, and the part of culture that calls itself “rational” refuses to recognize physiology as real unless it flatters their assumptions.

Interrogation doesn’t “bring out the truth” in me. It induces sympathetic overdrive and collapse dynamics that harm me and degrade my ability to communicate. When people see that and conclude “she’s changing her story” or “she looks dishonest,” what they are actually doing is punishing dysregulation. They are criminalizing my nervous system. They are treating the symptoms of trauma and disability as moral failure. And because they think lie detection is real—because they were trained by television, by pop psychology, by institutional myth—they feel entitled to their conclusion. They call it discernment. I call it discriminatory violence wrapped in certainty. It’s not just wrong; it’s dangerous. It primes other people to treat me and others like me as acceptable targets. It invites institutions to escalate. It licenses harm while pretending to be a search for truth.

11) Institutionalized “behavior detection” is a public example of science being ignored

A culture that believes in lie detection will keep reinventing it—especially in security contexts—because it feels intuitively satisfying. But government evaluations have repeatedly flagged the lack of scientific validation for many behavior-based indicators.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that TSA did not have valid evidence supporting much of its behavior detection approach.

GAO (2017): https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-608r GAO report PDF: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-17-608r.pdf Earlier GAO (2013) on SPOT program: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-14-159

This matters because it shows the core dynamic: institutions deploy “behavioral indicators” at scale, with high-stakes consequences, without robust scientific grounding. The result is predictable: false suspicion is distributed onto the people who deviate from narrow norms—often disabled, traumatized, neurodivergent, mentally ill, culturally different, or simply terrified.

12) What replaces coercive interrogation and vibe-based credibility judgments: evidence-based, rights-based interviewing

If society is serious about truth, it must stop using methods that are optimized for compliance and replace them with methods optimized for accurate information and human rights.

The Méndez Principles and the global shift away from coercion

The Principles on Effective Interviewing for Investigations and Information Gathering (commonly called the Méndez Principles, adopted in 2021) explicitly present a rights-based alternative to coercive interrogations and aim to prevent torture and ill-treatment while improving investigative effectiveness. These are not meant to apply to day to day, social interactions, but scientific and authoritative investigations.

Official site: https://interviewingprinciples.com/ Principles

These frameworks are not “soft.” They are disciplined. They treat interviews as a process that can contaminate evidence. They prioritize documentation, safeguards, presumption of innocence, and reliability.

The ethical pivot: coercion is not just abusive; it is epistemically corrupting. If you care about truth, you cannot treat nervous system destabilization as a tool.

13) What must change socially (not just legally): dismantling the myths

A society that keeps “lie detection” myths alive will keep re-enacting them in homes, clinics, workplaces, and online communities—even when police reforms happen. This requires cultural change, not just procedural change.

A. Stop treating stress behaviors as moral evidence

Nervousness, shutdown, confusion, flat affect, agitation, and memory disruption are not reliable indicators of deceit. They are indicators of state—physiological, psychological, contextual. Treating them as guilt is a category error.

B. Stop equating narrative inconsistency with lying

Memory is reconstructive. Retrieval is state-dependent. Stress can impair access. Trauma can fragment encoding and recall. People can remember more later, or remember differently as they stabilize. This is not a license for anyone to say anything; it is a demand that we stop treating “performance of linearity” as virtue and “dysregulated recall” as sin.

Stress and retrieval impairment review: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7879075/ Stress and episodic retrieval neurobiology: https://web.stanford.edu/group/memorylab/papers/Gagnon_YCN16.pdf

C. Stop letting “group consensus” replace evidence

Collective belief is not a fact generator. It is a power amplifier. It can be sincere and wrong—or strategic and malicious. Social hearsay can function like a mob epistemology: “everyone knows” becomes justification for escalating harm. That is how reputations are destroyed and how institutions become vehicles for discrimination.

D. Stop using coercive pressure as “truth production”

Interrogation that intentionally induces sympathetic overdrive, fear, exhaustion, or confusion is not a truth method. It is a compliance method with a known false-confession risk profile.

Kassin et al. white paper PDF: https://web.williams.edu/Psychology/Faculty/Kassin/files/White%20Paper%20online%20%2809%29.pdf APA resolution PDF: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2014/08/criminal-suspects.pdf

E. Recognize disability and trauma as protected contexts, not “suspicious behavior”

If your “credibility detector” fails disabled people, your credibility detector is not neutral. It is discriminatory. The correct response is not to demand that disabled people mimic neurotypical calm; it is to stop treating neurotypical calm as evidence of honesty in the first place.

Autistic adults misperceived as deceptive (NIH/PMC): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8813809/ Police interviews and autism (NIH/PMC): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10074602/

14) Conclusion: the human rights claim

Treating stress responses as guilt is not merely a “misunderstanding.” It is a social practice with predictable victims. It punishes the traumatized for being traumatized, the disabled for being disabled, and the neurodivergent for being neurodivergent. It turns physiology into suspicion and then pretends suspicion is truth.

Polygraphs do not read lies; they read arousal, and arousal is not specific to deception (National Academies, 2003). Demeanor-based deception judgments hover near chance (Bond & DePaulo, 2006; echoed in later summaries). Accusatorial interrogation can manufacture false confessions (Kassin et al., 2010; APA 2014). Institutions have deployed behavior-based suspicion systems without adequate scientific validation (GAO on TSA). Exoneration data repeatedly identifies false confessions and false accusations/perjury among contributing factors (National Registry of Exonerations annual reporting).

When society keeps treating these myth-based methods as legitimate, it normalizes harmful, coercive, discriminatory “credibility testing.” If we take evidence seriously and human rights seriously, this cannot remain acceptable “common sense.” It needs to end—not only in courtrooms, but in culture.

The Old Truth We Keep Forgetting: Don’t Judge

When all of the science, ethics, history, and harm are stripped down to their core, what remains is not a new revelation. It is an old one—so old that many cultures arrived at it independently, long before modern psychology, neuroscience, or law: do not judge.

This principle was never naïve. It was not born of ignorance about deception or harm. It emerged from a sober recognition of human limitation. To judge another person’s internal truth from external appearance, behavior under stress, social reputation, or secondhand narrative has always been dangerous. Cultures encoded “don’t judge” not because truth does not matter, but because humans are not built to reliably infer it in this way—and because the cost of getting it wrong is borne by the vulnerable.

Modern science has not overturned this principle; it has validated it. We now know that people are poor judges of deception, that stress distorts memory and behavior, that nervous systems vary widely, that disability and trauma alter presentation, that groups amplify bias, that coercion manufactures false narratives, and that confidence is not accuracy. We know that credibility is often socially constructed rather than evidentiary, and that punishment frequently precedes proof. None of this contradicts the ancient warning. It explains why it existed.

“Don’t judge” does not mean “ignore harm,” “abandon accountability,” or “refuse investigation when necessary.” It means something far more precise and demanding: do not confuse perception with truth. Do not elevate intuition into authority. Do not convert stress into guilt, difference into danger, or social consensus into fact. Do not turn the limits of your own knowledge into certainty about someone else’s interior reality.

This is the line that interrogation culture crosses. It is the line polygraphs cross. It is the line demeanor-based credibility judgments cross. It is the line “red flags” ideology crosses. In every case, the same error is repeated: the belief that moral or factual truth leaks reliably through behavior, and that the observer is entitled to interpret it. History shows what follows when this belief is normalized—wrongful punishment, exile, discrimination, and violence justified by certainty rather than evidence.

To live by “don’t judge” is not to live without discernment. It is to live with epistemic humility. It is to accept that much of what matters about another person is not available to inspection, testing, or performance. It is to refuse the role of evaluator in ordinary human relationships, and to recognize that respect is not something people earn by passing credibility tests—it is a baseline ethical stance.

This is especially critical in a world where trauma, disability, neurodivergence, and systemic harm are widespread. When societies forget “don’t judge,” they inevitably punish the very people whose bodies and minds cannot perform safety on demand. They call this realism. They call it discernment. But it is neither. It is an old error wearing new language.

The most responsible position—scientifically, ethically, and psychologically—is not hypervigilance, not suspicion, not constant evaluation, and not blind faith in intuition. It is this: treat people as truthful unless evidence demands otherwise; investigate when necessary without coercion; and refuse to mistake certainty for truth.

In the end, there is no technique that will save us from the risk of being wrong about others. There is only how we choose to relate to that risk. “Don’t judge” is not a moral platitude. It is the only stance that consistently reduces harm in a world where human truth cannot be cleanly detected—and pretending otherwise has always been the real danger.

Yes, sometimes lies are obvious. That does not validate intuition-based “lie detection.”

Sometimes deception is blatant: a claim collapses under basic verification, a timeline is impossible, a person contradicts themselves within minutes, or independent records clearly refute what was said. This matters, because critics of deception-detection skepticism often argue as if the only options are naïve trust or omniscient suspicion. Those are not the only options. The point is not that deception never reveals itself. The point is that most everyday “lie detection” operates on demeanor and stress behavior—and science repeatedly shows that this is error-prone, often near-chance, and strongly shaped by bias. A person can appear anxious and be truthful; appear calm and be deceptive; appear inconsistent due to stress, disability, or trauma physiology; or appear consistent because they rehearsed. The ethical duty, therefore, is not to pretend we can’t notice obvious contradictions; it is to stop treating our intuitive confidence as evidence—especially when disability, trauma history, power imbalance, or coercive conditions are present. When we already know someone has reasons to dysregulate under pressure, it becomes negligent to interpret dysregulation as guilt, and doubly negligent to treat social consensus about their “credibility” as proof. In short: obvious lies exist, but the everyday belief “I can tell” remains scientifically weak and ethically dangerous.

Manufactured credibility, manufactured guilt, and the violence of social certainty

“Credibility” is often treated as though it is a property of the person—something they either possess or do not. In reality, credibility is frequently a social product, shaped by status, aesthetics, conformity, charisma, narrative fluency, and who has allies. This is why collective judgment is not a substitute for evidence: groups can be sincerely wrong, strategically wrong, or incentivized to conform. In social systems, reputational cascades happen: one story becomes “known,” repetition becomes proof, and dissent becomes suspicious. The result can be a shared certainty that is psychologically intoxicating—people experience moral clarity, belonging, and the sense of participating in justice—while the underlying claims remain unverified or even fabricated. This is how wrongful social exile happens: people are punished not for what is proven, but for what has become socially legible as guilt. When disability or trauma responses are involved, the danger intensifies. A dysregulated nervous system can be interpreted as “untrustworthy,” and that interpretation can spread like a contagion. In that context, it is an ethical requirement—not an optional kindness—to consider whether “credibility” has been manufactured by bias, misunderstanding, coercion, or coordinated social pressure. Hearsay and collective vibe are not evidence; they are vectors for harm.

The ethical middle path: trust without naïveté; skepticism without cruelty

There are two symmetrical pathologies that societies normalize. The first is arrogant “intuition”: the belief that one can reliably detect lies from behavior, reaction, or social impressions, despite strong evidence of error. This belief produces unjust suspicion, and it also produces misplaced trust—because skilled deceivers are often not caught by demeanor-based judgment at all. No person is immune to being deceived; there is no special class of humans who can reliably see through others in ordinary life. Treating oneself as a human lie detector is not mental sharpness; it is overconfidence that predictably harms others and often damages one’s own reality-testing. The second pathology is the opposite extreme: permanent skepticism that withholds basic respect, accommodation, or belief until exhaustive proof is produced. In everyday life, this is corrosive. It turns relationships into interrogations and makes connection impossible. It also becomes discriminatory when directed at disabled people or trauma survivors: demanding proof of disability before accommodation, or proof of victimization before basic dignity, forces people into a punitive burden that many cannot meet in real time—especially under stress. Rights and ethics do not require a person to prove their humanity to earn humane treatment. The only sustainable way to reduce harm is to accept a difficult truth: in ordinary life we cannot reliably detect deception, and we cannot build healthy relationships by constantly trying. We must choose a baseline of trust and respect—while still allowing that in special circumstances (high stakes, clear contradictions, safety concerns, legal contexts) careful verification is appropriate. Verification is not the same as suspicion-as-a-lifestyle. The goal is not to become credulous; it is to refuse coercive epistemology—refuse practices that treat people as objects to be “tested,” especially when those tests are known to misfire against disability and trauma.

These dynamics are not only destructive to their targets; they are corrosive to the people and groups who adopt them. Living in a state of constant suspicion, moral certainty, and narrative enforcement degrades collective reality-testing and individual judgment. When groups or individuals treat intuition as evidence and dissent as threat, they do not become safer or wiser—they become brittle, fear-driven, and increasingly detached from corrective feedback. This is not strength or discernment; it is epistemic instability normalized as virtue.

Ordinary human relationships cannot function under evidentiary standards designed for courts or security screenings; importing those dynamics into daily life is not realism, it is a breakdown of ethical boundaries.

The “Red Flags” Ideology: Superstition Disguised as Safety

In recent years, a pseudo-psychological and quasi-spiritual ideology has gone viral in online culture—often framed as empowerment, self-protection, or emotional intelligence—under the banner of “red flags.” The claim is simple and seductive: if one maintains a state of constant skepticism, hypervigilance, and refusal to surrender trust, one will be able to detect danger, deception, or harm before it occurs. This belief system borrows the language of trauma awareness and psychology while discarding the actual science. What it produces is not safety, but a superstitious model of threat detection that mirrors—and amplifies—the same epistemic errors as interrogation culture and demeanor-based lie detection.

At its core, the “red flags” ideology assumes that danger announces itself through subtle behavioral cues, affective states, conversational irregularities, or perceived incongruence—signals that a sufficiently vigilant observer can learn to read. This is functionally identical to folk lie-detection beliefs: the idea that internal moral or relational truth leaks reliably through behavior, and that a watchful person can interpret those leaks correctly. As the scientific literature on deception detection, stress physiology, and social judgment already demonstrates, this assumption is false. Human beings are not reliable interpreters of internal states from external presentation, especially under conditions of uncertainty, fear, or projection. When people believe otherwise, they are not practicing discernment; they are engaging in overconfident pattern attribution.

The psychological cost of this belief system is substantial. Sustained hypervigilance is not a neutral cognitive stance; it is a stress state. Remaining perpetually alert for threat biases perception toward danger, increases false positives, and erodes the capacity for relational regulation. A person who refuses to surrender trust does not become more accurate—they become more suspicious. Suspicion feels like safety because it produces a sense of control, but control is not the same as truth. In fact, this posture often reduces accuracy by encouraging confirmation bias: ambiguous behavior is interpreted as evidence of danger because danger is already assumed. This is how ordinary human variance—awkwardness, nervousness, neurodivergence, trauma responses, cultural difference—gets reframed as moral or relational threat.

Crucially, the “red flags” framework also reproduces the same discriminatory dynamics discussed earlier in this article. Disabled people, traumatized people, neurodivergent people, and those with autonomic or cognitive differences are disproportionately flagged as “concerning” because their behavior deviates from idealized norms of calm, consistency, and emotional fluency. When these deviations are treated as intuitive warnings rather than as neutral differences, exclusion becomes morally justified. The ideology does not merely permit social exile; it aestheticizes it, recasting rejection and preemptive distancing as wisdom rather than harm. In this way, “red flags” culture functions as a socially acceptable mechanism for exclusion that requires no evidence and no accountability.

There is also a deeper epistemic danger: the belief that one’s intuition, once trained by vigilance, becomes especially trustworthy. This belief is psychologically reinforcing and socially contagious. People begin to mistake certainty for accuracy and confidence for insight. Entire communities can converge on shared narratives of danger without independent verification, mistaking consensus for truth. What emerges is not collective safety, but collective certainty divorced from evidence—a condition in which people feel morally authorized to judge, warn, and ostracize based on impressions alone. Historically, societies have always found ways to justify such dynamics; “red flags” simply provide a contemporary vocabulary.

At the same time, this ideology falsely promises protection from deception. It implies that constant suspicion will prevent betrayal or harm. The opposite is often true. Skilled deceivers are frequently adept at appearing calm, coherent, and reassuring—precisely the traits valorized by “green flag” aesthetics. Meanwhile, honest people under stress may appear uncertain, reactive, or inconsistent. Hypervigilance therefore fails in both directions: it falsely identifies danger where none exists and misses danger where it does. The belief that one can outsmart this reality through refusal to trust is not realism; it is magical thinking.

Equally harmful is the way “red flags” culture frames trust as naïveté and relational surrender as weakness. Human relationships cannot function as ongoing investigations. Trust is not the absence of discernment; it is the acceptance of epistemic limits. We do not build healthy connections by treating people as hypotheses to be tested indefinitely, nor by demanding proof of safety, goodness, disability, or victimization as a prerequisite for dignity. A life lived as a constant threat-assessment exercise is not psychologically healthy, nor is it ethically neutral. It externalizes fear onto others and normalizes evaluative surveillance as a mode of relating.

None of this is an argument against boundaries, accountability, or investigation when warranted. Special circumstances—credible evidence of harm, clear contradictions, legal or safety-critical contexts—require careful examination and verification. But a general lifestyle of suspicion, justified by the belief that danger can be intuitively detected through behavioral cues, is neither scientific nor humane. It is an extension of the same flawed logic that underlies coercive interrogation, polygraph superstition, and demeanor-based credibility judgments.

In the end, the “red flags” ideology offers a false bargain: permanent vigilance in exchange for safety. What it actually delivers is anxiety, misjudgment, relational impoverishment, and socially sanctioned harm—particularly to those whose nervous systems, communication styles, or histories do not conform to narrow expectations. A society serious about mental health, ethics, and human rights must be willing to say this plainly: hypervigilance is not wisdom, intuition is not evidence, and trust is not a moral failure.

On What This Ultimately Asks of Us

What is being named here is not merely a flawed practice, but a deeper epistemic failure—one that underlies many forms of harm that have been normalized in modern society.

Societies have a long history of moralizing whatever they cannot accurately measure. When humans lack reliable ways to know another person’s internal truth, they rarely accept uncertainty. Instead, they invent proxies. Calm becomes goodness. Fluency becomes honesty. Consistency becomes virtue. Dysregulation becomes guilt. Confidence becomes trustworthiness (or untrustworthiness). These substitutions feel practical, even rational, but they are not. They are metaphysical shortcuts—ways of avoiding the discomfort of not knowing while still feeling justified in judgment.

The problem is not simply that these shortcuts are inaccurate. It is that they are dangerous.

Much of what has been examined in this article—demeanor-based lie detection, interrogation culture, credibility judgments, polygraphs, hypervigilant “red flags,” social consensus as proof—rests on the same refusal to tolerate epistemic humility. Each promises a way to bypass uncertainty. Each claims to offer control. And each reliably produces harm, especially to those whose nervous systems, bodies, or histories do not conform to narrow norms.

There is an uncomfortable truth beneath all of this: many people cling to intuition, suspicion, and judgment not because they work, but because they protect the ego from helplessness. Admitting “I cannot reliably know” feels threatening in a world that equates certainty with strength. Yet without that admission, ethics collapses. When humility is rejected, power rushes in to fill the gap.

A culture that cannot tolerate uncertainty will always persecute nervous systems that visibly carry it.

This is why these issues extend beyond science, law, or psychology. They are about how a society decides who is readable, who is credible, and who is disposable. They are about whether we treat human beings as opaque subjects—with interior lives we cannot fully access—or as objects to be evaluated, tested, and sorted.

History is unambiguous on this point: the fantasy that we can reliably judge truth, danger, or worth from appearance and behavior has never been benign. It has always justified cruelty while calling itself wisdom.

What this work ultimately asks is not technical reform alone, but moral restraint. A willingness to relinquish the comfort of judgment. A refusal to convert uncertainty into suspicion. An acceptance that no amount of vigilance will grant special access to other people’s inner realities.

If there is a boundary for a humane society, it is this:

We must stop treating people as readable problems to be solved, and start treating them as human beings whose truths cannot be extracted through pressure, performance, or perception.

Science supports this. Ethics demands it. And history warns us what happens when we ignore it.

Constant evaluative vigilance is not mental health.

A person or group that cannot tolerate uncertainty, that continuously scans for deception, and that treats suspicion as virtue is not exhibiting discernment—it is exhibiting cognitive distress. Chronic suspicion degrades judgment, increases false positives, and creates self-sealing belief systems resistant to correction. At the group level, this can resemble collective paranoia or moral panic: dissent becomes suspect, certainty becomes identity, and evidence becomes secondary to narrative coherence. This is not safety. It is psychological instability normalized as wisdom.

The Author, Zilver, experiences Dysautonomia.

This work is not theoretical for me. I have been systemically and socially wronged by these myths—treated as deceptive, unstable, or untrustworthy because my nervous system does not perform credibility under pressure. Those judgments did not remain abstract; they resulted in social exile, institutional harm, and loss of material support to the point that sustaining survival became difficult. This should never happen to anyone. The purpose of this article is not persuasion for its own sake, but harm prevention: to interrupt a cultural logic that licenses character assassination under the guise of discernment.

Dysautonomia, vagus nerve dysregulation, and autonomic variance Disability, trauma, neurodivergence, and misread credibility Group credibility, hearsay, social consensus Ethical middle path Red flags ideology Don’t judge (final conclusion)

This placement ensures that dysautonomia is treated as central mechanistic evidence, not as an anecdotal or advocacy add-on.

Dedicated Section (insert as-is) Autonomic Variance and the Collapse of Demeanor-Based Judgment: Dysautonomia, Vagal Dysregulation, and the Myth of Behavioral Credibility

Demeanor-based judgments assume a false premise: that human autonomic regulation is sufficiently uniform for behavior under stress to be meaningfully compared across individuals. This assumption collapses in the presence of autonomic variance, particularly in conditions involving dysautonomia and vagus nerve dysregulation. When autonomic function itself is unstable, externally observable behavior becomes an unreliable proxy not only for honesty, but even for baseline cognitive access, emotional regulation, and speech production.

Dysautonomia refers to disorders of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which governs involuntary physiological processes including heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion, thermoregulation, and aspects of attentional and emotional regulation. These conditions are heterogeneous and can involve abnormal sympathetic activation, parasympathetic withdrawal or dominance, impaired baroreflexes, altered vagal tone, and unpredictable shifts between autonomic states.

Overview (NIH): https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/dysautonomia Clinical review: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459259/

In individuals with dysautonomia, autonomic state is not reliably coupled to external context in the way assumed by most social inference models. A neutral question can provoke tachycardia, breath dysregulation, dizziness, cognitive fog, speech disruption, or shutdown. Conversely, high-stakes situations may produce blunted affect or delayed responses due to parasympathetic dominance or dorsal vagal activation. These responses are frequently misinterpreted as evasiveness, dishonesty, lack of cooperation, or emotional incongruence—despite being physiological, not volitional.

The vagus nerve, a primary component of the parasympathetic nervous system, plays a key role in modulating heart rate variability, emotional regulation, social engagement, and stress recovery. Disruptions in vagal signaling can profoundly alter how a person appears and functions under stress.

Neurophysiology review: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5894396/ Heart rate variability and vagal tone: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5624990/

While simplified popular frameworks (e.g., reductive interpretations of polyvagal theory) often distort these mechanisms, the core scientific point is well established: autonomic regulation shapes cognitive access, speech fluency, emotional expression, and behavioral timing. When autonomic regulation is unstable, demeanor ceases to be interpretable in normative terms.

This has direct implications for credibility judgments. Many cues culturally associated with deception—pauses, fragmented recall, monotone or flattened affect, inconsistent eye contact, delayed responses, over- or under-arousal—are predictable consequences of autonomic dysregulation, particularly under evaluative threat. Stress-induced sympathetic overdrive can impair working memory and retrieval, while parasympathetic shutdown can reduce verbal output and responsiveness.

Stress and memory retrieval impairment: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7879075/ Acute stress effects on cognition: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5201132/

Importantly, these effects are state-dependent, not stable traits. The same individual may appear articulate and coherent in a regulated context and disorganized or mute under pressure. Demeanor-based systems—interrogation, credibility assessment, “red flag” vigilance—treat this variability as evidence of deceit or manipulation, when in fact it reflects context-sensitive autonomic collapse. The judgment error is not incidental; it is systematic.

Polygraph logic exemplifies this failure at an institutional level. Because polygraphs rely on autonomic arousal measures, individuals with dysautonomia or altered vagal tone are at heightened risk of false positives. The National Academies explicitly note that fear, anxiety, and physiological reactivity unrelated to deception undermine specificity—yet applied contexts routinely ignore individual autonomic differences.

National Academies, The Polygraph and Lie Detection: https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/10420

What makes this ethically severe is not merely inaccuracy, but predictable discrimination. When systems treat autonomic instability as suspicious, they effectively penalize people for the involuntary functioning of their nervous systems. This transforms disability into moral liability. It also incentivizes coercive stabilization demands—forcing individuals to perform calmness, coherence, and emotional regulation under threat—conditions that are physiologically unattainable for many.

The epistemic conclusion is unavoidable: behavior under stress is not a valid indicator of honesty when autonomic regulation itself is variable. Any framework—formal or informal—that ignores this reality is not just flawed; it is structurally incapable of fairness. In such contexts, “credibility” is not being assessed. It is being imposed.

Recognizing autonomic variance does not require abandoning truth-seeking. It requires abandoning the fiction that truth leaks reliably through behavior, especially under pressure. Until this shift occurs, demeanor-based judgment will continue to function as a covert mechanism of exclusion—mistaking nervous system difference for moral failure and calling the result discernment.